Contemporary sculpture: From steel to pixels and vice versa

By: Doreen A. Rios

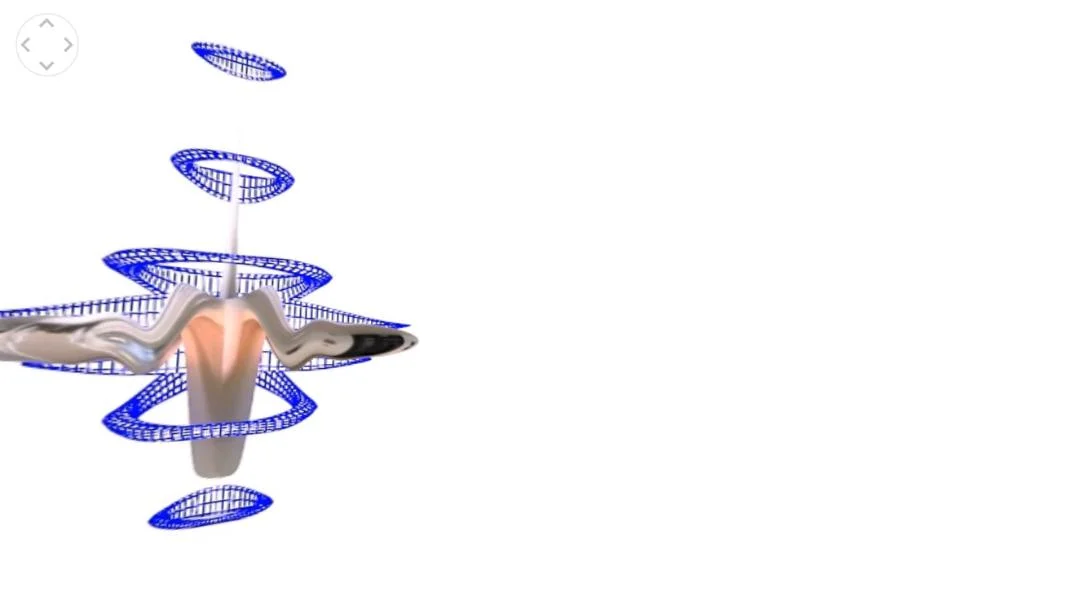

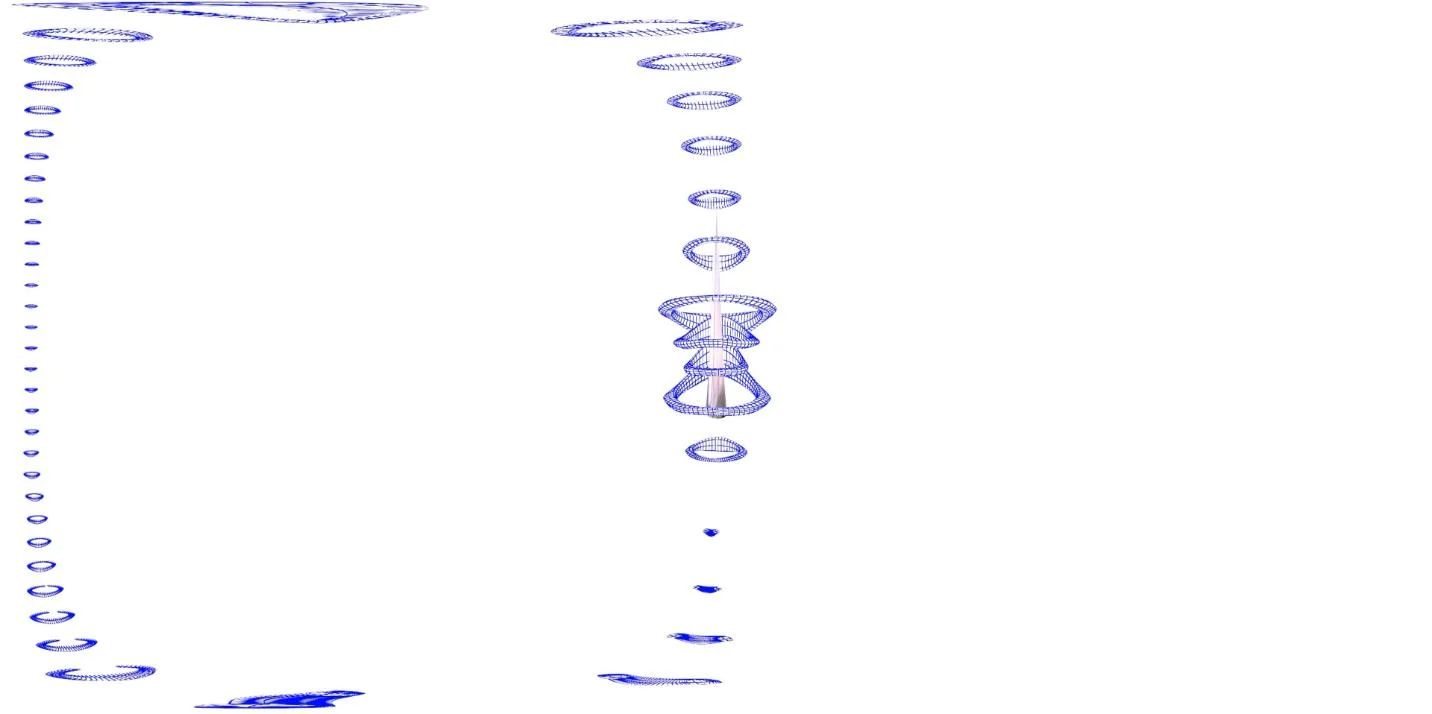

Fabric of Space (2016), Luis Antonio Tovar Salas

Introduction

It is clear: in contemporary art practices the mix and match of techniques is one of the most common ways of creation. The number of multidisciplinary artists has been constantly growing for the past couple of decades, to the point where contemporary art historians can’t sort out artists by the technique they use, something that was quite common until the 20th century. The current multidisciplinary/transdisciplinary culture has made contemporary artists closer to Renaissance figures such as Leonardo da Vinci or Michelangelo by not being able to provide a single area of expertise to their practice but treating them as ‘creative thinkers rather than skilled craftsmen’ (Getty Museum, 2009).

One of the reasons why the use of diverse techniques has been approached by several artists is the fact that new technologies have provided a larger set of tools that, when combined with the traditional art techniques, become a perfect complement to enhance certain features inside their artworks. However, if we focus on the outcome of the use of various techniques we can still identify plenty of them as part of a traditional art classification such as paintings, sculptures, photographs and engravings but in order to be understood as a whole, and in relation to other pieces, a sensible curatorial approach is essentially important. In words of Hans Ulrich Obrist – curator and art director of the Serpentine galleries – ‘curating as a profession means at least four things. It means to preserve, in the sense of safeguarding the heritage of art. It means to be the selector of new work. It means to connect to art history. And it means displaying or arranging the work. But it's more than that (…) The curator sets it up so that it becomes an extraordinary experience and not just illustrations or spatialised books.’ (Obrist, 2014). Therefore, for the audience to create connections between artworks and actively understand them as part of an art circuit, they need the expertise of a curator who is able to make meaningful links between artworks and encourages the blurring of unnecessary boundaries within them.

In this essay, I will focus in creating a direct link between virtual sculptures and traditional sculptures through a curatorial view by using two examples: Fabric of Space (2016) by Luis Antonio Tovar Salas and Torqued Ellipse IV (1998) by Richard Serra.

The digital world as a canvas for the physically impossible

The first exhibit I chose is Fabric of Space (2016) created by Luis Antonio Tovar Salas. This piece uses the technology of 360° video to create a hybrid of virtual reality within an augmented reality concept. Virtual reality has been around for at least three decades and gained popularity through the work of computer scientist Jaron Lanier who defined it as audio-visual experiences through computer-simulated environments which are commonly displayed in screens and more recently in headsets designed to enhance the piece (Lanier, 1986). This technique has evolved from being in a flat dimension restraining the movement by post-production values to a 360° visualisation where the viewer can move freely inside the computer simulation.

On the other hand, augmented reality refers to the addition of digital-based information to a physical environment. Unlike virtual reality, it requires a physical target (which is normally an image or pattern) to be activated and it uses the actual space that surrounds it as a canvas.

This term was coined in 1990 by Thomas Caudell who used it to describe a digital display used by aircraft electricians that blended virtual graphics onto a physical reality (Casella, 2009) and we could translate it to those practices that use digital-based images and audio to intervene a physical space in real-time.

In Fabric of Space, the artist used virtual reality to give life to a kinetic sculpture and then placed it inside the exhibition space. This is a site-specific project since it’s only supposed to be seen in this particular space (the Westside Foyer of Winchester School of Art) and in this sense, it is using augmented reality as a concept even if the outcome was fully created inside a computer simulation.

Fabric of Space (2016), Luis Antonio Tovar Salas

More interestingly, the artist looks to create an almost architectural experience by immersing a large-scale sculpture, made out of the foyer’s materials and digital textures, and blurring the separation between the space and the sculpture itself. The name of the piece explores the architectural immutability of the physical space and adds a layer of malleable materials that couldn’t be possible to gather any other way. The intention behind this piece is to provide a second layer of reality where we can interact with our surroundings in a new way, it encourages the viewer to become part of this alternate dimension where architecture behaves much more as a living creature rather than just an unmovable shelter. It questions the adaptability of the exhibition space and looks for new ways to intervene the so-called white cube.

We could divide this artwork in three stages:

First, we – as viewers – recognize that the space depicted is, in fact, the one we’re standing on.

Second, we approach the virtual sculpture in a similar way we would approach a physical sculpture.

Third, the movement of the sculpture eventually eats up the space becoming some sort of living black-hole that disrupts, changes and eventually spits out the physical space, and us with it.

Fabric of Space (2016), Luis Antonio Tovar Salas

This piece, as much as it is about the relation of time-space-movement, it is also about our role as active figures who are able to interrupt this relation and fill our surroundings with the fabric that’s been woven with our memories. It is a reminder of how fragile our surroundings can be and how we can intervene in breaking the chain of ideologies that seem to be suspended in time.

In times like these where it seems like there’s no way out of the vicious cycle of hate and rage, we are still capable of breaking the pattern and – as the artwork does with the space – re-think, re-purpose and finally mend these obsolete tactics that oppress new strategies from emerging.

The change of scale as a disruption of the white cube

The second exhibit I chose is Torqued Ellipse IV (1998) by Richard Serra. This piece is part of a series of sculptures developed throughout the 90’s and early 00’s and is a ‘logical conclusion to the architectural problems’ (The Art Story Contributors, 2008).

He started this series as a response to one of his visits to Rome, Italy where he recalls being inside a 15th century church, wondering if the elliptical form he saw on the floor, part of the architectural design, responded to the rotation of the ellipse he could see in the design above his head. However, after exploring the space he realized that the design was a regular cylinder, yet he became amused by how this space had tricked his eyes into thinking otherwise.

Serra became determined to create the shape he had imagined seeing in that space and explored with several materials just to find out that since that particular shape couldn't be seen in nature, nor architecture of the time. Therefore, he could only try doing this with an artificial assembly of weatherproof steel and aeronautical equipment.

Torqued Ellipse IV, Richard Serra, (ARCHISCAPES, 1998)

Furthermore, Serra was convinced that he didn’t have enough experience working with large-scaled sculptures and steel and tried to approach the architecture of New York, city where was living at the moment, as a source of inspiration; only to find out that the vocabulary of buildings with curvilinear forms was reduced to the Guggenheim Museum designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. This discovery only confirmed a deeper need for him to produce such a piece and challenge the limits of the modern architecture by inserting this elliptical sculptures right in the middle of one of the most loyal modern spaces: the white cube.

‘If you walk around the curve you don’t know how it’s going to round, it seems continuous and never-ending but a concave side like a gate reveals itself in its entirety, you know what the form is.’ (Serra, 2001).

Torqued Ellipse IV, Richard Serra, (NYTimes, 1998)

The decision of creating an interruption within the curved line of the sculpture was taken in order to create a space within space. The piece seems to have a great elasticity once you step inside and reveal the space leaning towards you or pointing away depending on where you stand. You can see that the ellipse on the floor is exactly the same as the ellipse above your head.

However, as the piece gets higher it starts to rotates in relation to itself but the curvature is the same all the way up.

This piece is an architectural exploration of the power of sculptures and the negative/positive space. As much as it is about trying out new materials and shapes, it is about the experience of the viewer as an active expeditioner of the sculptures. This piece has been used for both, the inside and the outside of exhibition spaces and each time it’s presented it created new connections with the architecture surrounding it yet, it never ceases to challenge idea of movement as well as it proposes to re-think how the audience should read sculptures.

Merging two worlds together

If we pay attention to the current state of curatorial proposals, we can still identify a clear line between digital-based and physical-based artworks. Normally the use of one would automatically repel the other, especially in fields like sculpture where the term is commonly regarded specifically to those practices that work with volumetric materials and where 3D printing seems to be the only appropriate digital technology to be considered a sculptural practice. Moreover, it is sensible to say that these decisions, based solely on out-dated definitions of what a sculpture is, are creating fictional boundaries that pause the natural evolution of arts in general.

Placing Fabric of Space (2016) and Torqued ellipse IV (1998) together inside an exhibition would mean to step outside the box of a so-called logical curatorial thinking, not only because they belong to different periods of time but because the creative minds behind them are very different figures. On one hand, we have Luis Antonio Tovar Salas, a Mexican emerging artist trained in architecture school who looks for immersive experiences through the creation of computer-simulated atmospheres, and on the other we have Richard Serra, a big name of American minimalism who made his career by experimenting with materials, scales and the use of space in an almost cinematographic way. Having this in mind, we could agree that not only they belong to a different set of time-space but that their artwork shares various antagonistic dualisms such as virtual/physical, emergent/established, post-digital/minimalist and the list could go on. However, as different as the artists might seem, they share a deep point in common which is the core idea to develop an architecturally challenging space by using a set of tools that haven’t been deeply explored before, particularly when it comes down to the creation of immersive spaces.

Even if Fabric of Space (2016) and Torqued ellipse IV (1998) seem very different, aesthetically and technically, they actually share a lot in common conceptually. Both of them belong to an architectural line of thinking and both of them look for a disruption of the white cube. It is reasonable to say that they even belong to a larger discourse of artistic experimentation which looks for creating active dialogues with the viewer by making him/her a central character who has the power to activate each artwork. Both have a wild restlessness of creating something that couldn’t exist any other way and they are convinced that the only way to approach their sculptures is by, literally, getting inside of them.

Furthermore, bringing together these two exhibits inside an exhibition space can also result in new ways of classifying art since the aim of the proposal is based on the idea of looking deeper into the concept and core ideas of artworks rather than attaching them to a certain technique and/or period of time.

Conclusion

It is crucially important for contemporary curators to question the traditional ways of putting a show together. We should ask ourselves whether if the classic methods are still valid or if we should be proposing different approaches to art.

It is necessary to turn our heads to the new techniques used by artists, especially to those that don’t respond to a well-researched way of display – by this I mean artworks living inside Apps, the internet, social media and so forth – because it is our role as curators to sort out a successful way to present them inside the exhibition space. Furthermore, we should also question the ways traditional curators have created links between artworks inside their shows, because it is our job to build bridges and create unexpected connections between the past, present and future.

If we replace architect with curator and design for curate in the quote ‘as an architect you design for the present, with an awareness of the past, for a future which is essentially unknown’ (Foster, 1995) we could pretty much summarize our main objectives as the translators between art and audience.

There’s clearly a big field of opportunity in merging together the digital and physical world, worlds which might not share a common vessel or medium but that share something that’s more important: a well-defined goal.

References

8 ways Richard Serra toys with our perception of space (no date) Available at: https://paddle8.com/editorial/8-ways-richard-serra-toys-with-our-perception-of-space/ (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

Burkeman, O. (2017) The guardian profile: Jaron Lanier. Available at: https://www.google.co.uk/amp/s/amp.theguardian.com/technology/2001/dec/29/games.academicexperts (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

Carter, I. and Bromwich, K. (2016) What inspires Hans Ulrich Obrist and seven other cultural tastemakers. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2016/aug/28/hans-ulrich-obrist-tastemakers-maria-balshaw-fabien-riggall-inspirations (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

Cassella, D. (2014) What is augmented reality (AR): Augmented reality defined, iPhone augmented reality Apps and games and more. Available at: http://www.digitaltrends.com/features/what-is-augmented-reality-iphone-apps-games-flash-yelp-android-ar-software-and-more/ (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

Center, D., Arts, the, York, N. and Cooke, L. (1998) Richard Serra, Torqued ellipses: Dia Center for the arts ... September 25, 1997 through June 14, 1998. Edited by Michael Govan and Mark Taylor. New York: Dia Center for the Arts,U.S.

Cook, S., Graham, B. and Gfader, V. (eds.) (2010) A brief history of curating new media art: Conversations with curators. Berlin: The Green Box Kunstedition.

Cooke, R. (2015) Hans Ulrich Obrist: “Everything I do is somehow connected to velocity.” Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/mar/08/hans-ulrich-obrist-everything-i-do-connected-velocity-interview (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

Corporation, A.W. (2017) Richard Serra. Available at: http://www.artnet.com/artists/richard-serra/ (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

Creswell, J.W. (2013) Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4th edn. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications : SAGE Publications.

D’Alleva, A. (2012) Methods & theories of art history. 2nd edn. London: Laurence King Publishing.

Ellis-Petersen, H. (2016) Hans-Ulrich Obrist tops list of art world’s most powerful. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/oct/20/hans-ulrich-obrist-tops-list-art-worlds-most-powerful-artreview-power-100 (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

Falconer, M. and Hodge, S. (2012) Why your five year old could not have done that: Modern art explained. London: Thames & Hudson.

Foundation, T.A.S. (2017) Richard Serra biography, art, and analysis of works. Available at: http://www.theartstory.org/artist-serra-richard-artworks.htm (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

Gagosian (2017) Richard Serra. Available at: http://www.gagosian.com/artists/richard-serra (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

The Guardian (2013) Jaron Lanier | technology. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/jaron-lanier (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

Kahn, J., Mouly, F., Yorker, T.N., Treisman, D., Malik, O., Davidson, A., Borowitz, A., Remnick, D., Osnos, E., Kolbert, E., Yaffa, J., Auletta, K. and Bernstein, J. (2015) Jennifer Kahn. Available at: https://www.google.co.uk/amp/www.newyorker.com/magazine/2011/07/11/the-visionary/amp (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

Leonardo da Vinci (Italian, 1452 - 1519) (Getty museum) (no date) Available at: http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/artists/511/leonardo-da-vinci-italian-1452-1519/ (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

LIeser, W., Baumgärtel, T., Baumgartel, T. and Dehlinger, H. (2010) The world of digital art. Germany: Ullmann Publishing.

Lunenfeld, P. (ed.) (2000) The digital dialectic: New essays on new media. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. 9 | P a g e

Max, D.T., Mouly, F., Yorker, T.N., Treisman, D., Malik, O., Davidson, A., Borowitz, A., Remnick, D., Osnos, E., Kolbert, E., Yaffa, J., Tomkins, C. and Mead, R. (2014) D. T. Max. Available at: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/12/08/art-conversation (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

McLuhan, M., Berger, J., Sontag, S., Munari, B. and Fiore, Q. (2008) The medium is the massage: An inventory of effects. London: Penguin Group (USA).

Mouly, F., Yorker, T.N., Treisman, D., Malik, O., Davidson, A., Kolbert, E., Borowitz, A., Remnick, D., Osnos, E. and Crouch, I. (2015) Man of steel. Available at: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2002/08/05/man-of-steel (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

Museum of modern art (2017) Available at: https://www.moma.org/explore/multimedia/audios/46/954 (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

Nissim, e. (2015) Torqued Ellipse IV (1998). Available at: https://archiscapes.wordpress.com/2015/05/13/richard-serra-the-space-between-art-site-and-viewer/torqued-ellipse-iv-1998-3/ (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

Obrist, H.U. (2014) Ways of curating. New York, NY, United States: Faber And Faber.

Obrist, H.U., Jeffries, S. and Groves, N. (2014) Hans Ulrich Obrist: The art of curation. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/mar/23/hans-ulrich-obrist-art-curator (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

O’Hagan, S. (2008) The interview: Richard Serra. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2008/oct/05/serra.art (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

Perry, G. (2016) Playing to the gallery: Helping contemporary art in its struggle to be understood. United Kingdom: Penguin Books.

Pickering, M. and Griffin, G. (eds.) (2008) Research methods for cultural studies. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Posted and Rouse, M. (2015) What is augmented reality (AR)? - definition from WhatIs.Com. Available at: http://whatis.techtarget.com/definition/augmented-reality-AR (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

Richard Serra - 284 artworks, bio & shows on artsy (1939) Available at: https://www.artsy.net/artist/richard-serra (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

Richard Serra | TTI London (2007) (2017) Available at: https://www.artsy.net/artwork/richard-serra-tti-london (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

Serra, R. (2017) Richard Serra biography, art, and analysis of works. Available at: http://www.m.theartstory.org/artist-serra-richard.htm (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

Smith, T. (2015) Talking contemporary Curating. United States: Independent Curators Inc.,U.S.

Steyerl, H. and Berardi, F.B. (2012) Hito Steyerl - the wretched of the screen. E-flux journal. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Tate (1988) Richard Serra (born 1939). Available at: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/richard-serra-1923 (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

visual-arts-cork (no date) Leonardo Da Vinci. Available at: http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/old-masters/leonardo-davinci.htm (Accessed: 6 March 2017).

(No Date) Available at: https://www.google.co.uk/amp/s/amp.theguardian.com/technology/2013/mar/17/jaron-lanier-digital-pioneer-rebel (Accessed: 6 March 2017).