The watermark as a manifestation of authorship in the circulation of digital images

By: Diego Ortega

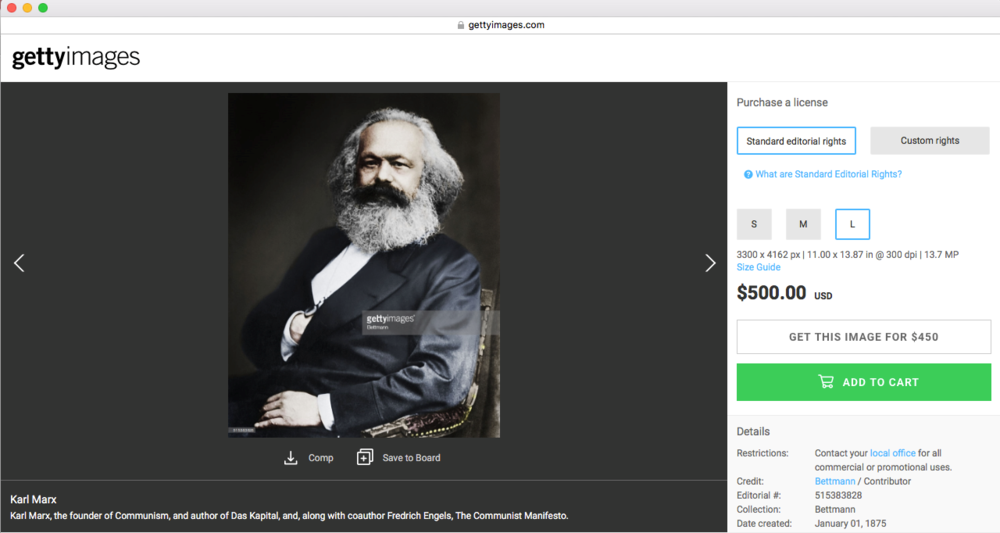

Screenshot taken from gettyimages.com with an image of Karl Marx created in 1875

Summary

The production, reproduction and circulation of images in the global context of the 21st century have unleashed new positions between the creator of images, digitally manipulated photography and the user/consumer of web 2.0. In this essay, I will address the relationship between the watermarks granted to digital images and their links with strategies for selling and appropriating photographs on the Internet. For this, I will start with the following questions: What is the role of copyright in the framework of the distribution of images online? Which are the legal and economic mechanisms for the protection of copyright that exist today? Is the watermark an effective system for photographers to maintain control over their images?

Introduction and background

The history of copyright begins in the printing of books in the eighteenth century. In England, the Statute of Queen Anne, whose full title is the Law for the Promotion of Learning, by allowing copies of books printed by the authors or buyers of such copies, during the times mentioned in it, was the first outline that legally understood the introduction of copyright in commercial practices.

The inventions of the industrial revolution were characterized by the search for commercialization and production aimed at mass audiences. These dynamics, already directed to the creation of a consumer society, gave rise to the registration of patents and the emphasis of copyright in the case of musical, literary and graphic works within the arts.

Walter Benjamin presents us in his work The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, the change of values that are granted to images, taking as a core theme their possibility of being replaced. Images prior to the eighteenth century acquired value in relation to the aura of the work, its historical relevance, and technical skill of the artist.

Later, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the possibility of reproducing a number of copies of a photograph broadened the perception of the image's historical, economic and social value. This indicates the concern of modern image producers because their images had a commercial value, which could compromise their work, to generate income as an economic model of sustenance. Benjamin addresses this precisely in chapter VI when he talks about the value of cult and the value of exhibition, specifically towards cinema, and how it acquires economic value through the number of reproductions and exhibitions that can be generated from it. "When the absolute weight falls on its exhibition value, the work of art becomes a creation endowed with completely new functions, among which stands out the one that is not known: the artistic function. Of which there is no doubt is that cinema is currently the most important medium to reach this conclusion." Benjamin W. (2003). In this context, authorship and author's rights acquire importance as they are the link between reproduction and economic value.

The second half of the 20th century, towards the 21st century

In the 1960s, pop artists like Robert Rauschenberg began to use popular images from magazines and television to incorporate them into their visual compositions. In the words of Rauschenberg, this process was organic: "I was bombarded with TV sets and magazines. With excesses of the rich. It seemed to me that honest work should incorporate all those elements. " Brucker J (2018)

It is interesting to observe how within this production logic the authorship of the images used in his collages was not relevant for the artist or for the discourse of the work. They were images that were taken for granted and when considering mass consumption, the effect and end of advertising use were more relevant than knowing who was behind them.

Later in the eighties, Sherrie Levine produced the After Walker Evans series as one of the most important symbolic statements about authorship and copyright. Levine, appropriating some photographs of Walker Evans, addressed one of the most important issues for postmodern discourses that referred to the authorship and ownership of the images. Precisely copyright did not allow him to sell these works so he had to resort to donate them. "The Estate of Walker Evans Foundation awarded its values to an institution (Metropolitan Museum of New York) in 1994. The collection includes the images of Levine that were acquired and banned for sale by The Estate of Walker Evans. Levine used his work to question artistic originality, The Estate of Walker Evans saw it as a violation of copyright "Jana R. (2001).

In parallel, communication networks and the first sketches of what would later become the Internet began to allow the exchange of information, mainly the digital exchange of texts and images. Marcel Danesi in his Dictionary of Media and Communication defines digital as: "any form of transmission in which a signal is sent in small and separate fragments" Danesi, M. (2009). The process of fragmenting and defragmenting data within the digital allows the use of metadata. Metadata, in the same Danesi dictionary, is defined as: "the information contained in a webpage that can be used by search engines to find relevant websites through hyperlinks" Danesi, M. (2009).

The use of the watermark was a mechanism quickly integrated into digital images to protect the authors of plagiarism of their photographs. The watermark in the images works in two ways:

- Visual: The watermark is represented as an element that is added to the composition of the photographs to avoid partial reproduction of the images. The watermark is placed as a post-production element that establishes the presence of an author or brand of the image.

- Digitally: information is entered about the author, date, place and photographic device with which the image was created within the metadata that makes up the image. This information can be written and visualized with specific software that allows seeing this information.

Currently, many photographers opt for these techniques for the protection of their images and to claim the authorship of these once they begin to circulate online. As an alternative to the protection and consensus of the use of intellectual property, the Creative Commons organization emerged in 2001, seeking to create legal licensing agreements that allow the use of certain contents in which, among other dynamics, they establish agreements between the creators and the users regarding what they can and can not do with their works. According to the official website of Creative Commons in 2009 estimated 350 million jobs that operate with CC licenses.

In this context, in 2003 Jon Oringer founded Shutterstock, a bank of images that through a subscription allows the download and use of images and video. Initially, that content is online with watermarks to guarantee the purchase of the content. Once the transaction is completed, the watermark is removed and the image is released for the client's use. Currently, Shutterstock is one of the most popular sites for downloading photos, vectors and videos.

Another popular site for its image bank for download with this commercial model is Getty images, founded even before Shutterstock with a similar transaction dynamics. The images also make use of the watermark to protect their images from theft.

Watermark, manifestations of capitalism in the context of autonomous images

Proof of the questionable role of copyright in contemporary society is the case by demand on the property rights of a self-portrait made by a monkey in 2011. This monkey was defended by PETA (People for the Deal Ethical of Animals). The organization defended the right of the monkey to be attributed the authorship of the photograph and not the owner of the camera, the British photographer David Slater. Cases like this unleashed the conversation about post-human photography. "In January 2016, the Federal Court of the United States declared that no one could be attributed the copyright because the animal is not legally a person and the copyright can only be claimed by whoever takes the photograph and not by the owner of the camera." 'Connell, M. (2016)

Self-portrait of female macaque in North Sulawesi, Indonesia who took the camera of photographer David Slater and photographed herself. 2011

Roland Barthes in his text, The Death of the Author states the following: "The author is a modern character, undoubtedly produced by our society, to the extent that, out of the Middle Ages and thanks to English empiricism, French rationalism and the personal faith of the Reformation, discovers the prestige of the individual or said in a nobler way, of the human person "Barthes, R (1987). If something characterizes the images circulating on the Internet is the little importance that the author has within the process of consumption and distribution. "The development of video technology will compromise the elitist position of traditional filmmakers and allow a kind of massive film production: an art of the people. Like the economy of poor images, imperfect cinema diminishes the differences between author and audience and fuses life and art." Steyerl, H. (2009) Today, do images which circulate online remain pristine, unaltered, authentic?

Anonymity is one of the main possibilities that allows the transmission of information over the internet. Therefore, it is important to stop and reflect. To contemporary producers is the recognition or attribution of certain authorship in the images still relevant? The answer to this question will refer us to the appeal of patents and auto rights, characteristic of modernity and monopolized corporations. In this context, how viable it is nowadays to carry out reappropriation exercises without incurring legal and criminal situations?

Could we understand that the value of the image of the 21st century should put authorship in the background by attributing value to images and paying more attention to other aspects of photography, especially after authorship has been a topic of interest for Postmodern artistic practices? At least within capitalism, it is difficult to reappropriate images without paying attention to the author and its context.

The censorship policies in the images, especially those that circulate in social networks, establish specific limits when it comes to sharing content with watermarks. The image distribution site dreamstime.com recently requested help from Facebook to remove or sanction pages that were using their images (with watermark included). These pages were aimed at the playful, and even artistic, creation of images, taking as raw material photographs with a watermark.

Conclusions

Digital images are inevitably part of a consumer process that we had not witnessed in previous centuries. The ease of reappropriation of content when interacting in virtual environments puts us socially in a dilemma that lies in the free distribution of content and information for non-commercial purposes and respect for the author, a prominent figure in monopolized societies, which aims to convert created in businessman inevitably. If this distribution and reappropriation of content do not involve economic transactions, we should rethink the policies that criminalize these activities. We live in a moment of medial transition, if history shows us the social changes inserted by photography, we must be willing to expand our conception of what makes up the value of the image in the coming decades.

In this sense, copyright becomes an inevitable issue within the dynamics of production, reproduction, distribution and sale of digital images. The artists that reappropriate the images on the internet, despite their watermarks, are aware of their violation of copyright laws and make it part of their speech, so that the watermark is transformed from a legal element to a visual element that reveals the origin of the image, in this sense, the watermark does not prevent the reproduction and distribution of images online and becomes a formal element of the image.

Bibliography

Benjamin, W. (2003). La obra de arte en la era de su reproductibilidad técnica. México, D.F.: Editorial Itaca.

Brucker, J. (2018). Robert Rauschenberg Artist Overview and Analysis. 18 de junio, de theartstory.org Sitio web: http://www.theartstory.org/artist-rauschenberg-robert-artworks.htm

Jana, R. (2001). IS IT ART, OR MEMOREX?. 19 de junio de 2018, de Wired Magazine Sitio web: https://www.wired.com/2001/05/is-it-art-or-memorex/

Danesi, M. (2009). Dictionary of media and communications. Nueva York, Estados unidos: M.e. Sharpe, Inc.

O'Connell, M. (2016). THE POSTHUMAN AND THE MONKEY SELFIE. 19 de junio, 2018, de Aarhus Universitet Sitio web: https://open-tdm.au.dk/ph/2016/10/the-posthuman-and-the-monkey-selfie/

Barthes, R. (1987). El susurro del Lenguaje. Barcelona, España: Editorial Paidos.

Steyerl, H. (2009). In defense of the poor image. 18 de junio de 2018, de e-flux.com Sitio web: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/